Graduate Program on Human Security of the University of Tokyo and Global Peace Association of Japan (GPAJ) held a seminar on the extent of reconciliation achieved in Rwanda with Dr. Kazuyuki Sasaki of Protestant Institute of Arts and Social Sciences.

Following the opening by Prof. Ai Kihara-Hunt, Associate Professor of the University of Tokyo and Secretary-General of GPAJ, guest speaker Dr. Kazuyuki Sasaki of Protestant Institute of Arts and Social Sciences spoke about his 13-year experience of living in Rwanda and working on reconciliation.

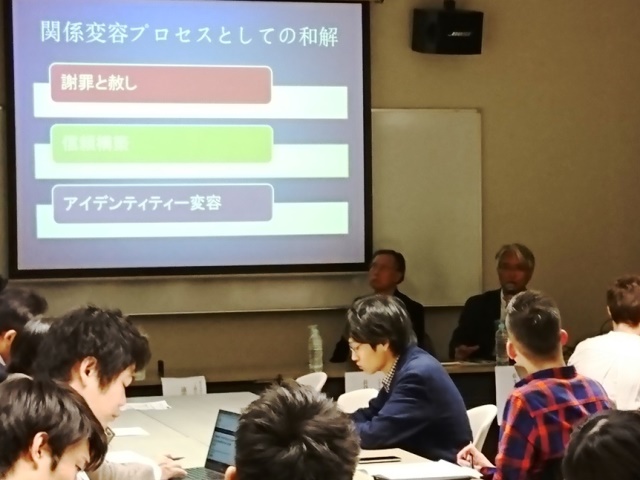

First, Dr. Sasaki questioned what ‘reconciliation’ is. He explained that various levels of reconciliation exist, namely reconciliation within oneself, between individuals and groups, or post-conflict reconstruction of society. There are also various depths of reconciliation along a continuum from thin/shallow to thick/deep forms of reconciliation. Reconciliation in the context of post-conflict societies may be considered along a continuum from nonviolent coexistence in the sense of existing together in the same place without fear of being attacked by ‘the other’ to cooperation based on trust required to work together and then finally to friendship based on a shared understanding of the past and a mutual commitment to shared future.

Dr. Sasaki reported that according to his research findings in the early 2000s, many ordinary Rwandans considered reconciliation to be the restoration of relationship between the perpetrators and the survivors based on a transaction of apology on the part of the perpetrator and forgiveness for the perpetrator’s wrongdoing on the part of the survivor.

For several years after the genocide against Tutsi in 1994, reconciliation was a taboo word in Rwandan society as it got such connotations as “forgiveness without justice” or power sharing with those who organized the genocide. The post-genocide government of Rwanda first put a strong emphasis on punitive justice through ordinary justice system. However, its approach to transitional justice gradually shifted to the direction of restorative justice through which unity of Rwandans would be restored. Accordingly, Gacaca courts operated as “reconciliatory justice” between 2002 and 2012.

Another critical challenge for post-genocide reconciliation in Rwandan society has been the restoration of national unity through forging a unified national identity. The 2015 policy for national reconciliation talks of the identity of the shared citizenship, culture and equal rights as the key elements of reconciled society.

Rwanda has chosen to use Gacaca court to pursue truth, justice and reconciliation. The practice of Gacaca court varied. It used work camp as part of penalties. The Court sentenced 1.6 million people guilty, but in a lighter category of alleged crimes, a lot of people were acquitted. In that way, the Court enabled a number of people to be released and commence normal lives.

Rwanda also emphasizes good governance and correct history sharing, and fights against divisionism, sectarianism and genocide ideology. There is a discouragement of competition between political parties. The Country rather works with consensus. Correct history sharing is based on the denial of ethnic groups. It is considered that the Hutu/Tutsi division was only created by colonial powers. In the discussion of genocide, it is emphasized that genocide was committed against Tutsi. Accordingly, although the government acknowledges the existences of victims with other identities, those with the Tutsi identity have been commemorated as the primary victims of the 1994 mass violence.

Currently, Rwanda has a rapid economic growth. It is positive that women are participating, and that national identity is being formed among the younger generation. On the other hand, there is criticism that Rwanda’s post-genocide justice was victor’s justice, and that reconciliation and justice has not been achieved fully. Reparation for genocide survivors is also not moving forward adequately. Gacaca Court has repaired some wounds but the assessment is also divided on the Court’ success among scholars.

Returning back to the original question: to what extent has reconciliation been achieved? Rwandan government reported that there has been remarkable achievement but that some problems remain. In the 2015 report on national unity and reconciliation, it claims that 92.5 percent of reconciliation has been achieved already. Dr. Sasaki explained various challenges that still stand out in the long road to reconciliation in post-genocide Rwanda, especially from the perspective of thick/deep form of reconciliation. For example, even though a great majority of perpetrators who have returned to their home villages made apologies before Gacaca court, a large proportion of them have not made an apology at the personal level in a way it is accepted by survivors they harmed during the genocide. On the other hand, he acknowledged a remarkable achievement of reconciliation in terms of peaceful coexistence by families of survivors and those of perpetrators. As for the sense of national identity, there seems to be a significant difference between the generation of Rwandans who experienced the genocide and that of those who were born after the genocide.

To Dr. Sasaki, there is no likeliness that genocide recurs, but there is no certainty that some violence will not happen in the future. He hopes that the new generation will overcome any inequality or seeds of potential conflict by peaceful means.

Prof. Mitsugi Endo of the University of Tokyo acted as a commentator, and introduced an NHK documentary that reported on reconciliation at the micro level. He opined that reconciliation is different from place to place, and that it is difficult to measure its achievement by a flat number.

In the long run, would violence recur? Prof. Endo stated that President Kagame is dealing with the international community very well by using good governance framework. It appears to be that, even if democratization is not achieved, there is not much criticism as long as good governance is kept and violence avoided. He also shared his opinion that President Kagame is using time very well. He can use 17 years to strengthen Rwandan identity, although this may not work if some event happens that challenges this very identity.

Prof. Sukehiro Hasegawa, former Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General and President of GPAJ, moderated the questions and answers session. He expressed his appreciation of Professor Sasaki’s insightful presentation and participants’ comments. He found the discussion centered around three issues: (1) the possibility of reconciliation, (2) the modality of governance, and (3) the community identify for maintenance of peace and stability.

Referring to the role of Gacaca Court system, Professor Hasegawa found it important to recognize two schools of thought about the efficacy of judicial system for achieving reconciliation. They were retributive justice and restorative justice. The former is the approach pursued by the UN to eliminate the culture of impunity by holding perpetrators accountable for crimes they have committed. Restorative justice, on the other hand, places more importance in pursuing truth and restoration of the relationship between offenders and victims by finding out what had happened rather than just prosecuting and punishing the perpetrators of crimes. This restorative approach was first taken by Nelson Mandela and has since been emulated by leaders of Timor-Leste and other countries. As mentioned by Dr. Sasaki, Rwanda shifted its approach from the retributive to restorative justice. The UN has insisted on applying retributive justice and established the International Criminal Court (ICC). This UN approach follows the theory developed by Immanuel Kant who had asserted that a society can achieve sustainable peace only if it maintained justice.

With regard to the modality of governance, Prof. Hasegawa explained the difference between good governance accepted as a model by the UN Commission on Good Governance in the 1990`s. The UN has since advocated democracy and the General Assembly adopted in 2005 the Consensus Document which referred to democracy as a desirable form of governance.

On the issue of identity, there are two models: UN model and American model. The former protects minority rights including by the establishment of quota, and the latter does not make quota. President Kagame has adopted an American model which advocates equality among all citizens regardless of their racial, ethnic, religious and ideological differences. He abolished the identity cards for Hutus and Tutsis, and recognized only one Rwandan people. Rwanda`s neighboring country of Burundi has incorporated the Malaysian or the UN model which protect the political and civil rights of minority ethnic groups. The certain percentage of seats of the National Parliament are allocated to different ethnic groups.

Professor Hasegawa concluded by stating that the moral responsibility for crimes committed by a previous generation cannot be disclaimed by their next generation as they were not those who actually committed crimes. For reconciliation to succeed, the leaders of nations and communities play a critical role and have a good chance in achieving reconciliation if they are committed to upholding truth and forgiveness as they have done by the leaders of Indonesia and Timor-Leste.