Graduate students from Afghanistan, Australia, Japan and Nepal assess the purposes and significance of CAVR, Serious Crimes Process, Commission of Experts, Truth and Friendship Commission and Commission of Inquiry with former Special Representative of the Secretary-General Sukehiro Hasegawa for Timor-Leste. This report is filed by Ms. Hanna Miura.

First, Ms. Hanna Miura explained the Comissao de Acolhimento, Verdade e Reconciliacao (CAVR) or the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation. CAVR was established in 2001 by UNTAET in order to seek the truth, promote reconciliation and to restore the dignity of the victims. CAVR was not a prosecutorial mechanism, but was successful in healing the wounds and in bringing the local communities together.

The Commission of Experts (COE), according to Mr. Patrick Kongmalavong, was established by the Security Council to review the prosecution of serious crimes in Timor-Lest. Three appointed experts submitted their report and recommendation which were not accepted as productive by the Government of Indonesia and Timor-Leste. The leaders of Timor-Leste had little will to raise tensions with Indonesia because they regarded Indonesia was going through a period of democratization at that time.

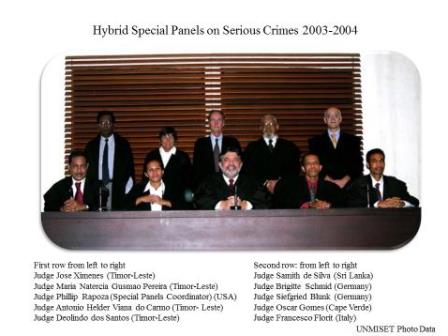

Mr. Jafar Atayee explained how the Serious Crime Process (SCP) was carried out by UNTAET. The SCP consisted of three different judicial activities: Court, Prosecution and Defense. Its main purpose was to investigate and prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, individual offences of murder, torture and rape, committed between 1st January and 25th October, 1999. However, since SCP had no authorization to arrest suspects who had fled to Indonesia, the “big fish” could not be caught. According to Professor Hasegawa, SCP had failed initially in providing “equality of arms.” Compared with the large number of prosecution staff, there were only a few UN volunteers on the defense side.

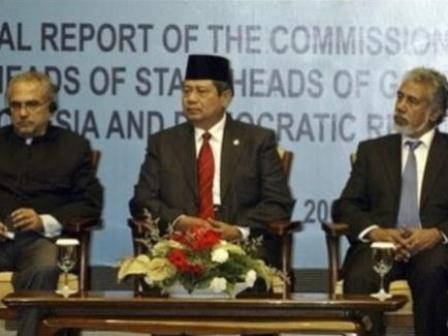

Lastly Mr. Joshi Dinesh explained the significance the Commission of Truth and Friendship, which was established by Indonesia and Timor-Leste. Since both governments of Indonesia and Timor-Leste wanted to move forward, this unique truth-seeking mechanism was built to ascertain what had actually happened and how the two countries could build their cooperative relationship.

Following each presentation, Professor Hasegawa provided additional information about the background of respective transitional justice processes. He mentioned that the United Nations did not want to support the Commission of Truth and Friendship as the policy of the United Nations was to pursue retributive justice in order to eradicate the culture of impunity.

At the later part of the class, students were tasked to perform as key stake holders. They represented the positions of Governments of Timor-Leste and Indonesia, international judges, UN officials, experts, local NGOs and victims. Furthermore, they were asked to discuss the merit of transitional justice Timor-Leste and lessons learned. Based on this role-play, students were able to gain an insight on the practical perspective, how conflict of interests among key players influenced the negotiation and how they were resolved.

In conclusion, Professor Hasegawa pointed out that “truth” can be used to accomplish both justice and reconciliation, and stressed the importance of balancing these two for sustainable peace.